LANCET COUNTDOWN ON HEALTH AND CLIMATE CHANGE

POLICY BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

The 2023 Lancet Countdown Brief for the United States (U.S.) presents country-level data on the health impacts of climate change from the 2023 Global Lancet Countdown Report. Building on this evidence, it recommends opportunities for advancing health and equity through climate action. The U.S. Brief is supported by a diverse group of health experts from more than 80 organizations who recognize that an urgent, deliberate, and health-centered transition away from fossil fuels and towards a climate-resilient society is fundamental to a healthy, just, and equitable future.

Introduction

Fossil fuel pollution and climate change have far-reaching and increasing impacts that threaten every aspect of physical and mental health for all communities in the U.S. and around the world.b1, b2 Climate change intersects with income inequality and systemic racism to further exacerbate these harms, driving disproportionate impacts across the lifespan for low-wealth communities, people of color, Indigenous populations, and other susceptible populations.b3, b4, b5 ** As such, fossil fuel pollution and climate change are fundamental issues of economic, racial, and intergenerational justice.

Current climate change is principally driven by human-generated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced primarily by the burning of fossil fuels (coal, oil, and gas) and other combustible fuel sources.b6 Air pollution from fossil fuel combustion and the climate change that results from GHG emissions cause and worsen numerous health conditions, from heart and lung diseases to neurological and kidney conditions, mental health disorders, allergies, infectious diseases (Box 1), pregnancy complications and poor birth outcomes, injuries, and death.b7

Without urgent action to reduce GHG emissions and air pollution, communities across the U.S. will experience increased threats to health and well-being. The 2023 Lancet Countdown indicators reveal concerning trends in the observed health impacts of climate change (Table 1),b2 highlighting the imperative to accelerate a just transition away from fossil fuels, and the profound opportunity to improve health and equity by taking climate action.

**For a fuller discussion of how climate change intersects with and compounds multiple forms of systemic inequity and discrimination to disproportionately harm different marginalized communities and populations, please see the 2022 U.S. Brief.

The State of Climate Change and Health in the United States

The U.S. experienced an unprecedented number of devastating climate-driven events in 2023b8, b9 including intense heat, wildfires, and flooding. These events led to myriad physical and mental health harms, premature death, and health system disruptions – the full extent of which are yet to be quantified. The summer of 2023 was the hottest on record,b10 in part due to human-caused climate change.b11 In Maricopa County, Arizona, for example, nearly 425 people are estimated to have died from heat-related causes between May and Octoberb12 and hundreds of additional deaths remain under investigation. However, evidence indicates that the impact of such heat events on the local population could be significantly greater, as official statistics often severely underestimate the true mortality burden of heat,b13 and extreme heat has far-reaching health impacts beyond the immediate death toll.b7

Extreme heat also fuels and compounds droughts,b14 (Indicator 1.2.2) which were especially severe in southern and midwestern states in 2023,b9, b15 and wildfires (Box 2). In August 2023, the Hawaiian Firestorm destroyed the town of Lahaina on Maui Island in the deadliest U.S. wildfire in over a century.b9 Extreme storms are also becoming more frequent and intense due to climate change, and numerous severe storms struck the Central U.S. while Hurricane Idalia was the strongest hurricane the Florida Big Bend region had experienced in 125 years.b9 Unprecedented rainfall, including record-breaking events in Vermont and California, led to floods, landslides, and immense community disruption.b9

Box 1

Climate change is increasing the likelihood that infectious diseases in the U.S. will spread to more geographies (Indicator 1.3, Table 1). Locally acquired cases of malaria and dengue – diseases transmitted by climate-sensitive mosquitoes – are re-appearing in parts of the U.S. Four states reported locally acquired cases of malaria in 2023, including the first known case in Arkansas since eradication, and the first cases in Texas and Maryland in nearly 30 and 40 years, respectively.b16, b17, b18, b19 Locally acquired malaria cases were also reported in Florida.b20 Recently, locally acquired cases of dengue were reported in Arizona,b21 California,b22 Florida, and Texas.b23 While the total number of cases remains small, the trajectory will need to be monitored as conditions for disease spread become more favorable.

Box 2

Air quality improved in the U.S. in recent decades, with major associated improvements in public health, in large part due to federal policies like the Clean Air Act.b24 These gains are now slowing and in some cases reversing due to climate changeb25 – especially as it contributes to more frequent and intense wildfires.b26 Since 2016, wildfire smoke is estimated to have reversed around 25% of prior air quality progress in the U.S. and more than 50% of progress in some western and midwestern states.b27

Wildfire smoke is more harmful to health than non-smoke particulate pollution.b28 Smoke is a significant contributor to worsening health trends,b29 including increased heart and lung diseasesb30 and higher mortality,b31 and may disproportionately affect marginalized communitiesb32 and people with existing health conditions.b33

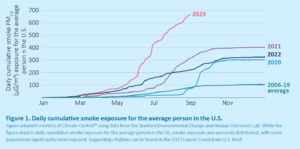

The U.S. experienced record wildfire smoke exposures in 2023 (Figure 1). In June 2023, historic climate change-fueled wildfires in Canada exposed almost one-third of people in the U.S. – more than 100 million – to unhealthy air quality.b34 Nationally, emergency department visits for asthma were nearly 20% higher than expected during the smoke events,b35 with even greater increases in areas most affected by the smoke.b36, b37 For instance, levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) were more than 12 times higher than historical baselines in some parts of New York, with emergency department visits increasing two to three times above recent levels.b36

Figure 1. Daily cumulative smoke exposure for the average person in the U.S.

Figure adapted courtesy of Climate Centralb38 using data from the Stanford Environmental Change and Human Outcomes Lab. While the figure depicts daily cumulative smoke exposure for the average person in the US, smoke exposure was unevenly distributed, with some populations significantly more exposed.

Table 1

Air Pollution

Fossil fuel combustion is contributing to premature deaths

- Indicator 3.2.1

In 2020, fossil fuel combustion accounted for approximately 41.5% of all premature deaths attributable to human-caused fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the U.S.* - Indicator 4.1.4

The monetized value of premature deaths from fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in 2020** was estimated to be $151 billion.***

*Data for 2020 was previously presented in the 2022 U.S. Brief and is reported again here using updated methods.

** Based on an estimated 32,400 deaths from PM2.5 in the U.S. in 2020.

***Using 2022 USD.

Heat

Climate change is increasing exposure to hotter temperatures

- Indicator 1.1.1

2022 was the warmest year ever recorded in the U.S. Average U.S. summer temperatures in 2022 were 2.3°F (1.3°C) warmer as compared to 1986-2005.

Older adults and infants in the U.S. face increasing heat exposure*

- Indicator 1.1.2

Adults 65 years and older experienced a 138% increase in exposure to heatwaves** annually (172 million more person-days***) from 2013-2022 compared to 1986-2005, meaning that each older adult, on average, was exposed to an additional 2.8 heatwave days per year as compared to the historical baseline. - Indicator 1.1.2

U.S. infants under 1 year experienced a 61% increase in exposure to heatwaves** (19 million more person-days***), meaning that each infant, on average, was exposed to an additional 3.2 heatwave days per year from 2013-2022 compared to 1986-2005. - Indicator 1.1.2

In a scenario in which temperatures are kept to under 3.7°F (1.3°C) of heating, heatwave exposure fro people over age 65 is projected to be 5 times greater by mid-century (2041-2060 average). - Indicator 1.1.5

Among adults 65 years and older, heat-related mortality is estimated to have increased 88% in 2018-2022 compared to 2000-2004, reaching an estimated 23,200 deaths in 2022. In the absence of climate change-induced temperature increases, heat-related mortality would have been expected to increase 25% across this period.**** - Indicator 4.1.2

In 2022, the monetized value of these heat-related deaths in adults 65 years and older in the U.S. was estimated to be more than $11 billion.*****

*Older adults and infants are more susceptible to the adverse health impacts of extreme heat exposure (2022 U.S. Brief).

**Heatwave is defined as a period of two or more days where both the minimum and maximum temperatures are above the 95th percentile of the U.S. climatology (defined as the 1986–2005 baseline).

***Person-days refer to the cumulative number of days of heatwave that people were collectively exposed to (e.g., if 100 people were each exposed to 5 heatwave days, there would be 500 person-days of exposure).

****In a counterfactual scenario holding temperature constant and accounting for only population changes.

*****Based on an estimated 23,200 deaths in 2022 in the U.S. from heat-related mortality in adults 65 years and older.

Increasing economic burden of heat in the U.S.

- Indicator 1.1.4

In 2022, heat exposure in the U.S. led to the loss of 2.9 billion potential labor hours, a 54% increase from the 1991-2000 average. The construction sector accounted for 43% of these losses, 33% in services, 14% in manufacturing, and 10% in agriculture - Indicator 4.1.3

In 2022, $81 billion in potential income was lost in the U.S. from reduced labor due to extreme heat. 45% of the losses occurred in the construction industry, 32% in the service sector, 15% in manufacturing, and 8% in agriculture.

Urban centers in the U.S. lack adequate green space

- Indicator 2.2.3

Green space promotes numerous health benefits and reduces heat exposure.b7,b39 In a study of 49 U.S. urban centers, 25 were classified as having moderate or higher levels of greenness* in 2022. This was a decline from 30 urban centers with moderate or higher greenness in 2015.

*Green space, or “greenness”, is an area covered by vegetation like grass or trees rather than human-made surfaces like asphalt, providing benefits to air quality and reducing urban heat and flooding. Greenness was estimated using a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), a satellite-based method.

Infectious Disease

Climate change is contributing to the expansion of conditions for infectious disease spread

- Indicator 1.3

The transmission season for Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax – two parasites that cause malaria – lengthened by 39% and 33.65%, respectively, in U.S. lowland areas** in 2013–2022 compared to 1951–1960. - Indicator 1.3

The ability of Ae. aegypti – the mosquito that can carry the dengue virus – to transmit dengue had more than doubled in 2013–2022 compared to 1951–1960 in the U.S. (as defined by the basic reproductive number, R0*). It is now greater than 1, signifying the potential for the disease to spread. - Indicator 1.3

9.3% of total U.S. coastline was suitable for Vibrio transmission in 2022. The total area of U.S. coastline suitable for Vibrio transmission, at any point during the year, was 44.4% higher than average suitability from 1982–2010.

*The transmission potential (R0) determines how likely one infection is to lead to another, or the transmissibility of a disease.

**Any part of the U.S. that is <1500 meters above sea level is considered lowland.

Drought

The amount of U.S. land under extreme drought is increasing

- Indicator 1.2.2

The amount of land classified as experiencing at least three months of extreme drought per year increased 22% from 1951 –1960 to 2013 –2022. In 2022, 11% of U.S. land area experienced over three months of extreme drought. Drought has numerous implications for health, including increased risk of infectious diseases, impaired sanitation, and threatened water security.b2, b14

Sea Levels Rise

Sea level rise has implications for health

- Indicator 2.3.3

In 2022, 1.78 million people lived less than 3 feet above current sea levels. Sea level rise has implications for health, including impacts from flooding, contamination of drinking water, infectious diseases, and worse mental health.b2, b7

Progress on Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The U.S. was the second-highest emitter of CO2 in 2021

- Indicator 4.2.5

In 2021, the U.S. was the second-highest emitter of CO2 by both production- and consumption-based accounting,* contributing 13.4% and 16.0% of the world’s production- and consumption-based CO2 emissions, respectively. - Indicator 4.2.5

In 2021, the U.S was one of the five leading emitters of primary PM2.5, by both production- and consumption-based accounting, contributing 2.9% of the world’s production-based PM2.5 emissions and 5.2% of the world’s consumption-based PM2.5 emissions.

*Consumption-based accounting assigns emissions to countries based on how they are consuming goods and services, independent of where in the world those emissions were actually produced.

Total renewable energy is increasing but remains minimal

- Indicator 3.1.1

Renewable energy* use accounted for less than 3% of total energy supply in the U.S. in 2020, an increase over previous years. Coal use, while declining, accounted for 11% of total energy supply in 2020.

*The Lancet Countdown indicator uses data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and defines renewable energy as wind and solar. The U.S. Energy Information Association (EIA) currently defines renewable energy as including hydroelectric and biomass, and thus reports a higher percentage of energy supply coming from renewable sources.b40

Electricity-driven transportation is minimal but rising

- Indicator 3.1.3

The percentage of total electricity-driven transportation in the U.S. increased from 0.03% to 0.1% between 2015 and 2020. Since the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015, fossil fuel usage as a percentage of total U.S. transport energy has remained steady at 93%.

Fossil fuel company production strategies are out of line with the Paris Agreement and U.S. climate targets

- Indicator 4.2.6

As of February 2023, ExxonMobil’s planned operations would generate 55% more GHG emissions than would be compatible with an annual “emissions budget” aligned with 1.5°C of average global heating. In 2040, expected emissions would rise to 217% more than a 1.5°C emissions budget.

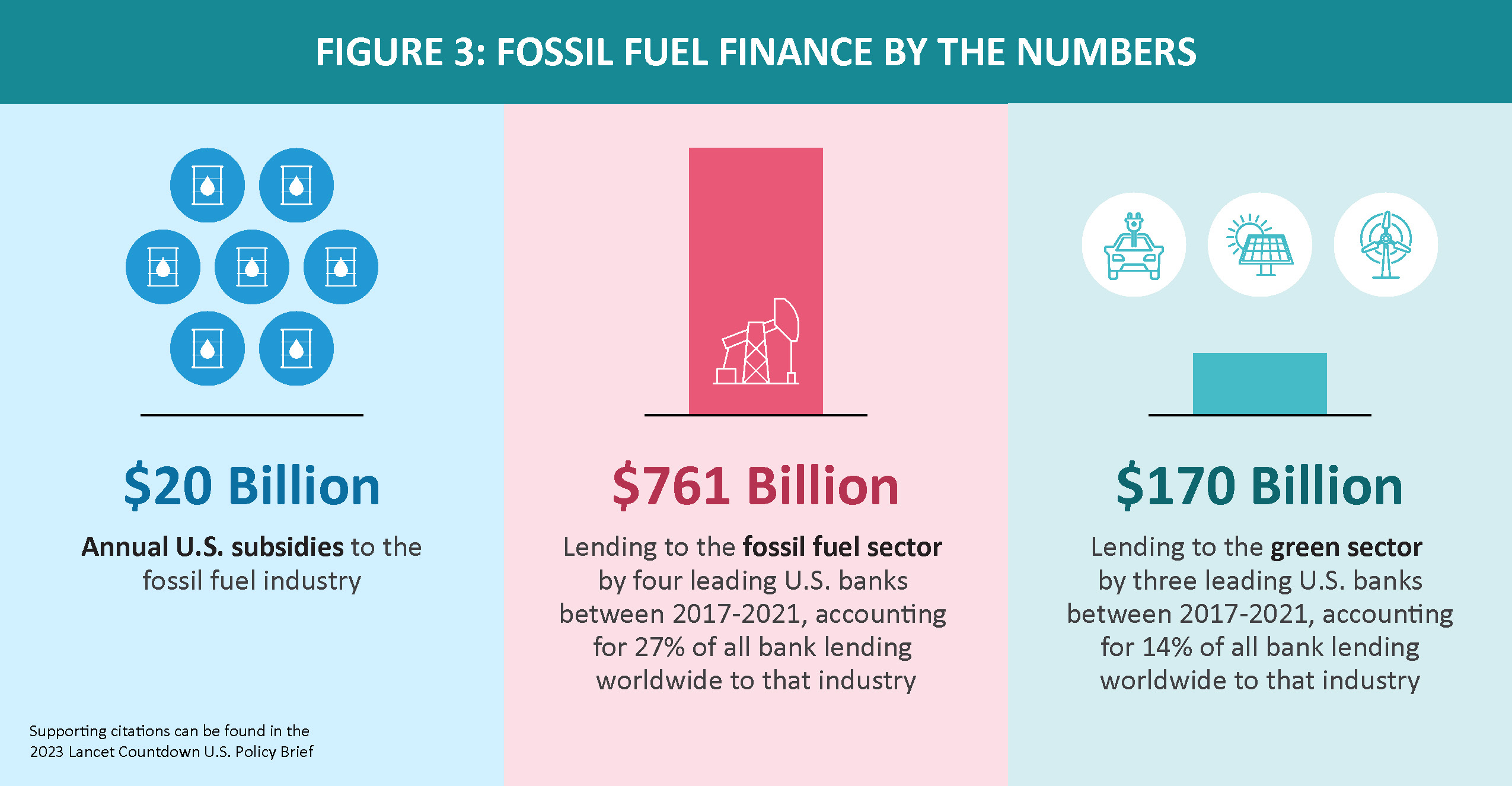

U.S. banks are global leaders in fossil fuel sector lending, while green sector lending reached an all-time high in 2021

- Indicator 4.2.7

Between 2017-2021, four U.S. banks (Citi, Bank of America, JP Morgan, Wells Fargo) lent more than $761 billion to the fossil fuel sector* (average of $152 billion per year), accounting for 27% of worldwide bank lending to that industry. - Indicator 4.2.7

Between 2017-2021, three U.S. banks (Citi, Bank of America, JP Morgan) lent more than $170 billion to the green sector (average of $34 billion per year). Lending to the green sector steadily increased over the past 12 years, reaching an all-time high of $76 billion in 2021. - Indicator 4.2.7

Over the past 12 years, JP Morgan was the leading U.S. bank lender to the fossil fuel sector, lending 8.2 times more to the fossil fuel sector than to the green sector.**

*Fossil fuel sector lending is defined as “being directed towards exploration, production, operations, and marketing activities in oil and gas.”

**Green sector lending is self-identified by the issuer as funding a project or activity with an environmental or sustainability-oriented goal, such as renewables and energy efficiency, green building and infrastructure, agriculture and forestry (reforestation, land use), and other sustainability activities (clean water, waste management).

All indicator data in this table comes from the 2023 Global Lancet Countdown Report. For detailed information regarding the indicators and indicator methods, please see the Global Lancet Countdown Report Appendix. We thank the authors of the Global Lancet Countdown Report for their work in developing the indicators and providing the regional analyses.

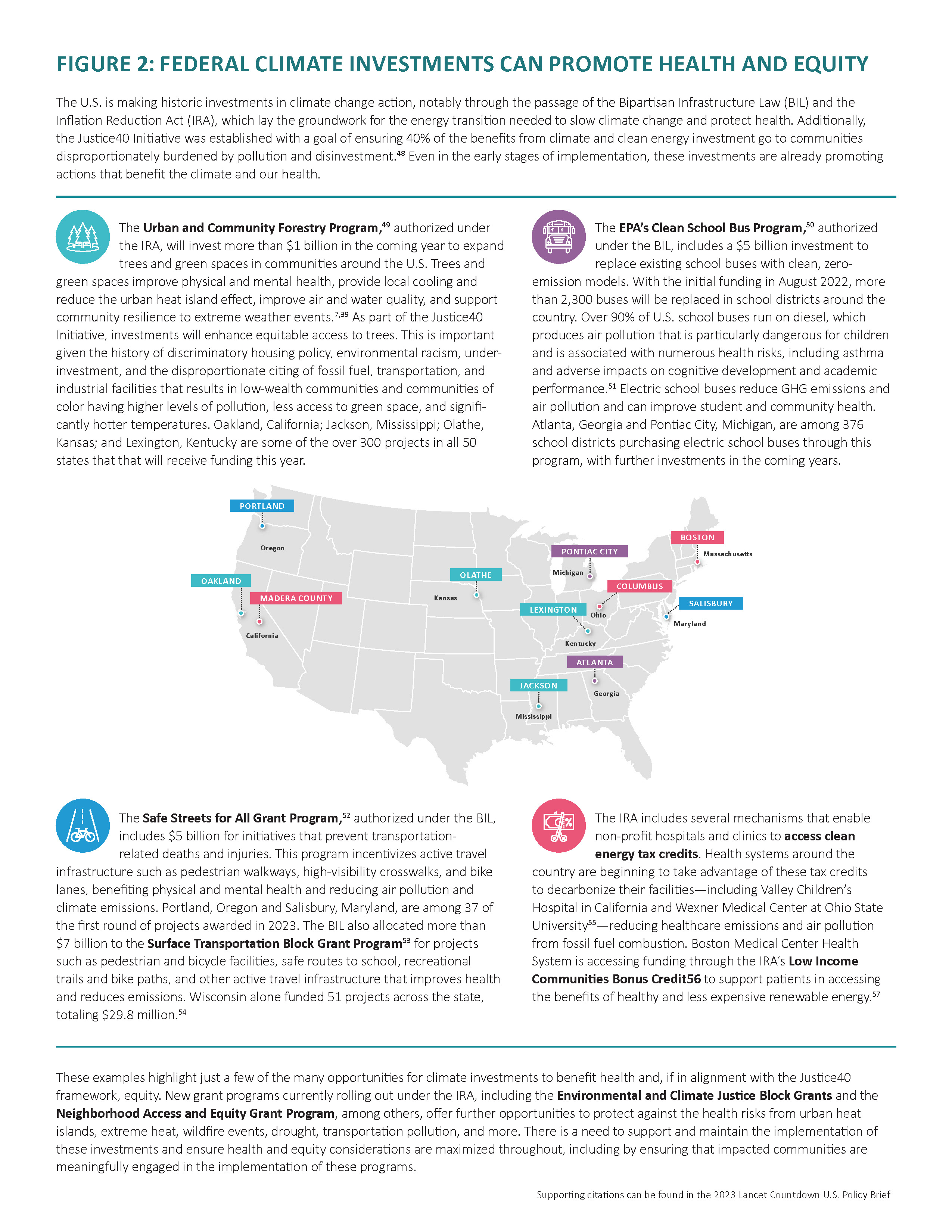

Strengthening Efforts to Address Climate Change and Ensure a Healthy, Equitable Future

The past year was one of climate progress in the U.S. In August 2022, the U.S. passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which, alongside the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act, is enabling potentially transformative investments in clean energy, electrification, community resilience, and environmental justice. These investments could dramatically reduce air pollution, limit the health impacts of climate change, and catalyze additional action (Figure 2). By 2030, the IRA is estimated to reduce economy-wide CO2 emissions by 35 – 43% below 2005 levels, and reduce electric power sector emissions 49 – 83% below 2005 levels.b41, b42 States around the country are also passing climate change legislation in energy, transportation, buildings, and other sectors.b43, b44

Despite these gains, the U.S. remains a leading contributor to global GHG and particulate air pollution emissions and has among the highest per capita CO2 emissions in the world, surpassing China (Indicator 4.2.5, Table 1).b45 Accelerating towards zero emissions as rapidly as possible will result in immense health benefits through improved air quality and by limiting climate change, while every fraction of a degree of heating will worsen health outcomes and health inequities.b46, b47

This is a critical moment to secure and build on this recent progress. The health community can play a leading role, both in ensuring the IRA and other climate policies are successful in the face of political threats and in advancing the health- and equity-oriented implementation of climate policies.

Recommendations for Promoting Health and Equity through Climate Action

A rapid transition away from fossil fuels is needed to save lives, protect health and wellbeing, avoid the worst impacts of climate change, and maintain a healthy environment. The U.S. Brief highlights four priority areas for action.

- Recommendation 1: Take action to reduce air pollution, simultaneously reducing the health risks from fossil fuels and reducing GHG emissions.

- Recommendation 2: Protect health from future climate change by ending fossil fuel exploration and extraction, rapidly phasing out fossil fuel use, and ending fossil fuel subsidies.

- Recommendation 3: Make protecting and enhancing human health a central consideration in the transition to renewable, non-combustion energy.

- Recommendation 4: Invest in adaptation to protect people’s health from the harms of climate change.

Figure 2: Federal climate investments can promote health and equity

Recommendation 1: Take action to reduce air pollution, simultaneously reducing the health risks from fossil fuels and reducing GHG emissions.

Recommendation 1: Take action to reduce air pollution, simultaneously reducing the health risks from fossil fuels and reducing GHG emissions.

We must make every effort to safeguard against the established and severe health risks associated with fossil fuels. Air, water, soil, noise, and light pollution from fossil fuel extraction, production, transportation, and consumption processes contribute to health impacts, including asthma and other respiratory diseases, heart disease, some cancers, poor birth outcomes, cognitive effects, and premature death.b3, b4, b7, b58, b59

Air pollution is a leading driver of fossil fuel-related health harms (Indicator 3.2.1, Table 1). Further action is needed to protect the health for all communities, especially those disproportionately burdened by air pollution due to historical and persistent systemic and structural inequities. This can include: strengthening clean air protections for all air pollutants, most critically, establishing more stringent rules for particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone levels in line with the best available evidence on health harms; strengthening measurement and reporting of inequities in air pollution exposure; and enhancing enforcement of air quality standards. Policies to limit exposure to fossil fuel air pollution, such as setback requirements for fossil fuel infrastructure, can also reduce mortality.b60

Inequities in exposure to air pollution persist despite overall improvements in air quality in the U.S.b61 b62, b63 Unhealthy levels of air pollution and its associated health risks are disproportionately concentrated in communities of color, low-wealth communities, and historically redlined neighborhoods.b64, b65, b66, b67, b68 Reducing GHG emissions in line with policies like the IRA will not, on its own, reduce inequities in air pollution exposure.b69 Thus, explicit attention to the health equity impacts of pollution reduction strategies is needed to ensure these approaches do not maintain or deepen inequities even as overall emissions decline.b70 Enhancing funding for community air quality monitoring in under-resourced communities could, for example, significantly improve the implementation of targeted policies to enhance air quality and promote public health in these areas.

Because of the significant health risks of pollution across the fossil fuel life cycle, and the clear causal relationship with worsening climate change, policies that seek to reduce emissions while continuing the use of fossil fuels (e.g., through emissions control or carbon capture technology) will not have the same health benefits as policies that reduce the use of fossil fuels, and may have adverse health and health equity impacts.b7, b71

Recommendation 2: Protect health from future climate change by ending fossil fuel exploration and extraction, rapidly phasing out fossil fuel use, and ending fossil fuel subsidies.

Recommendation 2: Protect health from future climate change by ending fossil fuel exploration and extraction, rapidly phasing out fossil fuel use, and ending fossil fuel subsidies.

Globally, fossil fuel projects currently in planning and in development could, if realized, emit GHG emissions far exceeding the limits consistent with a 1.5°C rise in global temperatures. The U.S. oil and gas sector is expected to make the most significant contribution between 2020-2050 (see for example Indicator 4.2.6, Table 1; Figure 3).b72, b73 New fossil fuel development actively threatens the health of people in the U.S. and around the world. It is incompatible with achieving stated climate goals and is inconsistent with cost-effective pathways to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century.b74

To protect humanity from the worst impacts of climate change, it is critical to phase out existing fossil fuel production and end investments in new fossil fuel infrastructure in a managed and equitable way.b73, b75 This can include establishing ambitious and binding targets to phase out coal, oil, and gas production and use, including on public lands by 2035; prohibiting new and expanded fossil fuel infrastructure on public lands and waters; and phasing out U.S. exports of coal, oil, and gas, which reached a record high in 2023.b76 These policies can drive significant, near-term health improvements. For example, the closure of a coking coal plant in Pittsburgh significantly improved air quality and reduced heart-related emergency department visits by 42% a week after its shutdown.b77

These actions must be accompanied by rapidly and substantially curbing investments in, and subsidies for, fossil fuels and other combustion sources of energy (Figure 3).b78, b79 Investments by banks, retirement and pension funds, and other financing institutions are used to fund fossil fuel exploration and production (Indicator 4.2.6, Table 1; Figure 3), furthering dependence on polluting energy sources and contributing to worsening future climate change. These investments also undermine the energy transition by displacing finance that could support the scale, accessibility, and affordability of healthy, non-combustion renewable energy.

As part of its broader climate mitigation goals, the health sector must likewise reevaluate its financial strategies and align health investments with the sector’s mission to protect health. This includes strategies such as divesting funds from fossil fuel-related companies or industries.

Additionally, it has been well documented that the fossil fuel industry uses its investments and lobbying to promote misinformation and delay policy and regulation that could address the health crisis from climate change and fossil fuel pollution.b80, b81, b82, b83 Prior effective public health campaigns – notably on tobacco and lung cancer – successfully used media advocacy linked with local and state policy campaigns to explicitly counter industry influence and disinformation.b84, b85 Similar strategies deployed in relation to the fossil fuel industry could inform the public about the health harms of fossil fuel pollution and climate change, and build the social and political will necessary to accelerate action on climate and health.

Figure 3: Fossil fuel finance by the numbers

Recommendation 3: Make protecting and enhancing human health a central consideration in the transition to renewable, non-combustion energy.

Recommendation 3: Make protecting and enhancing human health a central consideration in the transition to renewable, non-combustion energy.

Renewable energy, while rapidly increasing, remains a small share of the overall U.S. energy portfolio (Indicator 3.1.1, Indicator 3.1.3, Table 1). As the cost of renewables declines, it is economically feasible to transition to clean, healthy, non-combustion energy systems.b86, 87 Additional investments and policy reforms are needed to ensure the potential health benefits of new climate investments are achieved and to accelerate a just and equitable transition (Box 3).

Financial incentives for renewable energy adoption must be accompanied by clear goals for transitioning away from fossil fuels, including firm, near-term timelines for zero-emission energy, transportation, and buildings; implementation of 100% clean, renewable electricity standards for utilities; and fossil fuel-free government procurement policies.b75 The speed of electrification of transportation and buildings will be a large determinant of the ability of the U.S. to make the transition to healthy energy. This will require large-scale investment in the development and deployment of new electrification infrastructure paired with strong regulatory and policy changes that expand transmission, reform permitting for clean energy, remove barriers to non-fossil fuel energy infrastructure, and expand incentives for – and equitable access to – electric vehicles and building technologies. Policies that help avoid fossil fuel use, such as energy efficiency standards and electrification standards for new construction, are also critical to ensure the efficiency and feasibility of the clean energy transition.b88

Investments should prioritize and deliberately target GHG emission reductions that deliver the greatest and most immediate health benefits. For example, electrifying heavy-duty vehicles can reduce air pollution and generate large health benefits, particularly for historically marginalized communities.b89 Promoting safe, accessible, and active modes of transportation (e.g., walking, biking) also yields significant climate and health benefits.b90 Electrification and energy efficiency in buildings and transportation can improve air quality and energy security, and thus improve health.

Current federal funding for climate and health research fails to meet urgent needs.b91 It is critical for federal agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and others, to invest in research on all new energy technologies and the implications of their adoption for public health. This should include health impact and life cycle assessments for new technologies themselves and for various deployment scenarios. A notable focus should be on avoiding the substitution of fossil fuels with false solutions that harm health or increase health inequities and identifying ways to eliminate or minimize potential unintended health harms.b92 This will help ensure the adoption of actions that maximally reduce air pollution and GHG emissions.

Box 3

Many communities rely on fossil fuels for economic and energy security. Provisions are needed to ensure that the energy transition, which can bring significant, immediate health benefits, is equitable and beneficial to all communities.b93

Many families around the country experience energy insecurityb94, b95, b96 that harms their health directly and through multiple social and economic determinants of health. The cost of newly installed renewable energy is now below that of fossil fuelsb97 and provides a feasible alternative for affordable, reliable, and accessible energy for all. Policymakers need to work alongside communities throughout the decision-making process to ensure policies meet the specific needs of impacted communities. Investments, including access to — and benefit — from hosting renewable energy generation, need to be directed toward the most impacted communities. Programs to support electrification and energy efficiency must be accessible and affordable to families, schools, health facilities, and other essential groups.

Recommendation 4: Invest in adaptation to protect people’s health from the harms of climate change.

Recommendation 4: Invest in adaptation to protect people’s health from the harms of climate change.

Even with immediate action to reduce GHG emissions, there remains an urgent need to address the health impacts that are already being experienced and that will continue to rise in the coming decades.b98 Investing in adaptation and resilience today is critical to protect health and wellbeing. Increasingly frequent and severe climate events make it more challenging to protect people and recover from climate-related disasters, and accelerating climate disruption may exceed our capacity to effectively protect public health.

Solutions are available to improve community resilience and reduce the impacts of climate change on health, such as through urban greening, distributed community-based renewable energy, and emergency preparedness and response.b7 Yet, adaptation investments fall far behind what is needed to protect people from worsening climate-driven health hazards, both in the U.S.b39 and globally.b99 For example, while 2023 saw historic federal investments in climate change, none of this funding was specifically dedicated to state health agencies to carry out climate adaptation activities. This shortfall in funding is a barrier to implementing climate and health adaptation solutions.b100, b101

Substantially greater and timely investment is needed to scale up solutions across impacted communities and to build the capacity of communities and public health systems to take action on climate and health adaptation, including for instance through the CDC’s Climate-Ready States and Cities Initiative.b102 Adaptation investments should target the most impacted communities and prioritize community-led solutions.

The U.S. also has a role to play in supporting adaptation globally through its contributions to global climate finance to support impacted countries in implementing climate mitigation and adaptation solutions. The U.S. must significantly scale up its contributions to climate finance, in line with global commitments and its contributions to historic emissions.b7, b103

Conclusion

There are many reasons for cautious hope as parts of the U.S. start to move toward a deliberate and rapid transition to healthy, clean, and renewable energy.b104 There is not only viability in the clean energy economy, but also vitality – improving health for all and advancing health equity – if this becomes core to decision-making. In parallel, there must be health protections to address the harmful impacts of climate change today and into the future.

Young people, in particular, have rallied around this imperative,b105, b106, b107 holding a transformative vision for the future that protects the health and well-being of current and future generations. The opportunity – and responsibility – in our current moment is to swiftly accelerate a health- and equity-centered transition to clean and healthy energy across every sector of society. The time is now.

Acknowledgements

THE LANCET COUNTDOWN

The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change is a multi-disciplinary collaboration monitoring the links between health and climate change. It brings togethers lead researchers from 43 academic institutions and UN agencies in every continent, publishing annual updates of its findings to provide decision-makers with high-quality evidence-based recommendations. For its 2023 assessment, visit https://www.lancetcountdown.org/.

THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION

The American Public Health Association (APHA) champions the health of all people and all communities. It strengthens the public health profession, promotes best practices, and shares the latest public health research and information. The APHA is the only organization that influences federal policy, has a nearly 150-year perspective, and brings together members from all fields of public health. In 2018, APHA also launched the Center for Climate, Health and Equity. With a long-standing commitment to climate as a health issue, APHA’s Center applies principles of health equity to help shape climate policy, engagement, and action to justly address the needs of all communities regardless of age, geography, race, income, gender, and more. APHA is the leading voice on the connection between climate and public health. Learn more at www.apha.org/climate.

U.S. Policy Brief Authors: Naomi S. Beyeler, PhD, MPH, MCP; Paige Knappenberger, MA; Jeremy J. Hess, MD, MPH; Renee N. Salas, MD, MPH, MS.

Additional Team Acknowledgements: Support, Logistics, & Review: Kelly P. Phouyaphone, MPH, PMP; Copy Editing: Vivian Taylor, MDiv, MPP; Olivia Amitay, B.S.; Spanish Copy Editing: Juan Aguilera, MD, PhD, MPH; Website Design: Huck Strategies. Thank you to the Climate and Health Foundation for their generous support.

Review on Behalf of the Lancet Countdown (alphabetical): Camile Oliveira; Marina Romanello, PhD; Maria Walawender, MSPH.

Review on Behalf of the American Public Health Association: Katherine Catalano, MS.

Science and Technical Advisors (alphabetical): These science and technical advisors provided technical and review assistance but are not responsible for the content of the report, and this report does not represent the views of their respective federal institutions.

Caitlin A. Gould, DrPH, MPPA; Rhonda J. Moore, PhD; Ambarish Vaidyanathan, PhD, MSEnvE.

U.S. Brief Working Group Reviewers of Brief (alphabetical): Ploy Achakulwisut, PhD; Juan Aguilera, MD, PhD, MPH; Susan Anenberg, PhD; Mona Arora, PhD, MSPH; Gaurab Basu, MD, MPH; Laura Bozzi, PhD; Jonathan Buonocore, ScD; Robert Byron, MD, MPH; Linda D. Cameron, PhD; Amy Collins, MD; Cara Cook, MS, RN, AHN-BC; Shelbi Davis, MPH, PMP; Michael A. Diefenbach, PhD; Caleb Dresser, MD, MPH; Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, MPH; Matthew J. Eckelman, PhD; Donald Edmondson, PhD, MPH; Luis E. Escobar, DVM, MS, PhD; Meghana Gadgil, MD, MPH, FACP, FHM; Julia M. Gohlke, PhD; Yun Hang, PhD, MS; Adrienne L. Hollis, PhD, JD; Heidi Honegger Rogers, DNP, FNP-C, APHN-BC, FNAP; Ans Irfan, MD, EdD, DrPH, ScD, MPH, MRPL; Shaneeta Johnson, MD, MBA; Harry Kennard, PhD; Kevin Lanza, PhD; Vijay Limaye, PhD; Rachel Lookadoo, JD; Edward Maibach, MPH, PhD; Benjamin Miller, MD; Leyla McCurdy, MPhil; Lisa Patel, MD, MS; Jacqueline Patterson, MSW, MPH; Jonathan Patz, MD, MPH; Ellen Peters, PhD; Rebecca Philipsborn, MD, MPA; Alixandra Rachman, MPH; Angana Roy, MPH; Caitlin Rublee, MD, MPH; Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH; Liz Scott; Emily Senay, MD, MPH; Jodi D. Sherman, MD; Cecilia Sorensen, MD; Vishnu Laalitha Surapaneni, MD, MPH; J. Jason West, PhD, MS, MPhil; Kristi E. White, PhD, ABPP; D’Ann L. Williams, DrPH, MS; Jennifer Monroe Zakaras, MPH; Carol Ziegler, DNP, APRN, NP-C, APHN-BC.

U.S. Brief Infographic Creators

Figure 1: Daily cumulative smoke exposure for the average person in the U.S. – Courtesy of Climate Central using data from the Stanford Environmental Change and Human Outcomes Lab.

Figure 2: Federal climate investments can promote health and equity – Naomi S. Beyeler, PhD, MPH, MCP; Nova Tebbe MPA, MPH; Jonathan Patz, MD, MPH. Designed by Huck Strategies.

Figure 3: Fossil fuel finance by the numbers – Data from the 2023 Lancet Countdown Global Report. Designed by Huck Strategies.

Recommended Citation

Lancet Countdown, 2023: 2023 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Policy Brief for the United States of America. Beyeler NS, Knappenberger P, Hess JJ, Salas RN. Lancet Countdown U.S. Policy Brief, London, United Kingdom, 20 pp.

Introduction State of Climate Change – Box 1: Malaria & Dengue – Box 2: Intensified Wildfires New Findings: Key U.S. Specific Indicators – Air Pollution – Heat – Infectious Disease – Drought – Sea Levels Rise – Progress on Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions Strengthening Efforts to Address Climate Change and Ensure a Healthy, Equitable Future Recommendations – Recommendation 1: Reduce Air Pollution – Recommendation 2: Protect Health – Recommendation 3: Centralizing Health in the Renewable Transition – Recommendation 4: Invest in Adaptation Conclusion Acknowledgements