LANCET COUNTDOWN ON HEALTH AND CLIMATE CHANGE

POLICY BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

OCTOBER 2022

The State of Climate Change and Health in the United States

Climate change and its primary driver – burning fossil fuels – have created an accelerating crisis of far-reaching health impacts including heart and lung disease, heat-related illness, infections, food- and water-borne ailments, poor pregnancy outcomes, adverse mental health impacts, injuries, and death. There are also significant implications for health and well-being with disruption to health care delivery; population displacement; interruptions in education, employment, and other community services; and societal-wide economic harm.

While everyone is at risk, the health impacts of climate change are not experienced equally. Structural racism and economic injustice amplify climate change-related health inequities by increasing susceptibility and exposure to climate threats and reducing the adaptive capacity of communities targeted by discriminatory policies. Climate change is one of many compounding health crises facing communities and health systems across the U.S. today, furthering the urgency of decisive policy action to protect health. The 2022 Brief focuses on four areas of health impact: health harms of poor air quality, heat-related illness, infectious disease, and mental health.

Burning fossil fuels drives poor air quality, harms health, and increases health inequities.

Fossil fuel combustion produces climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions and harmful air pollution. Air pollution harms every major organ system in the body, causes heart disease and childhood asthma, and is a major cause of illness and death in the U.S. Children are uniquely susceptible. Due to systemically unjust policies, there are deep racial and income inequities in air pollution exposure. In addition, climate change worsens air quality by increasing exposure to wildfire smoke, dust, ground-level ozone, and pollen – all of which harm health. The illness and death caused by air pollution impose a major economic toll.

Extreme heat is becoming more severe and there are wide inequities in heat-related illness and death.

Heat is the leading cause of weather-related death in the U.S. Susceptibility to heat-related illness is heightened among children, pregnant people, older adults, and people living with pre-existing illness. Extreme heat can threaten children’s physical and mental health, impair their ability to learn in school, and threaten safe outdoor play. Extreme heat exposure during pregnancy is associated with poor birth outcomes. People from communities of color and low-wealth communities, outdoor workers, people experiencing homelessness, and people who are incarcerated are often more exposed to extreme heat and thus more often suffer from heat-related illness and death. Strategies exist at the household, community, and city levels that can protect against extreme heat and other climate-related health harms, yet not all people and communities have equitable access to the resources and strategies known to minimize heat risks.

Climate change is increasing the threat of infectious diseases.

Early evidence suggests climate change may be linked with increases in the incidence of more than half of infectious diseases worldwide. Water-borne disease threats are increasing as warmer water is more conducive to the growth of pathogenic bacteria such as Vibrio spp. Increased flooding can contaminate drinking and recreational waters, contributing to higher rates of gastrointestinal illness. Climate change is also expanding the areas in which disease-transmitting ticks and mosquitoes live, increasing the suitability for the transmission of pathogens that cause Lyme disease and West Nile.

Climate change harms mental health and well-being.

Climate change is associated with increased risk of depression, stress, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, grief, substance abuse, disempowerment, and hopelessness. Children, young people, and rural and Indigenous communities are particularly impacted._1_

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Policy Recommendations to Advance Health and Equity in the U.S. Climate Change Response

The U.S. is at a turning point on climate change. The Inflation Reduction Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and CHIPS and Science Act create tremendous new federal investments to support a transition to clean energy and build climate resilience. City, tribal, and state governments are innovating and scaling up local climate action. Yet the U.S. continues to pursue climate strategies inconsistent with health and equity goals – subsidizing fossil fuels, expanding oil and gas leases, and underfunding climate change and health programs.

Our ongoing reliance on fossil fuels causes tremendous health harm. A rapid transition to clean energy and away from from fossil fuels can result in immediate health benefits including cleaner air and safer, more resilient communities, while also protecting against the worst climate change-related health threats. To best protect health and equity, these goals must be prioritized in climate policy implementation. The U.S. Brief offers five recommendations to ensure that historic climate actions and investments protect health today and create a healthier and more equitable future for all people in the U.S.:

Achieve a zero-emission energy sector and prioritize air quality improvements in the most impacted communities. The U.S. must rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 57% to 63% by 2030 to to achieve national emissions consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement. This will require additional action and investment by all levels of government. To advance health, implementation of clean energy policies must ensure that all communities have equitable access to healthy, clean energy solutions, and that air quality improvements target the most impacted communities.

Achieve a zero-emission energy sector and prioritize air quality improvements in the most impacted communities. The U.S. must rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 57% to 63% by 2030 to to achieve national emissions consistent with the goals of the Paris Agreement. This will require additional action and investment by all levels of government. To advance health, implementation of clean energy policies must ensure that all communities have equitable access to healthy, clean energy solutions, and that air quality improvements target the most impacted communities.

Accelerate the transition to a zero-emission transportation system that equitably benefits health. Decarbonizing transportation will bring immediate health benefits including cleaner air and more physical activity. To maximize health equity, federal and state governments can: increase funding for zero-emission public transit systems and active transportation infrastructure (e.g., walking, biking); strengthen fuel efficiency and pollution standards; expand state incentives to accelerate equitable electric vehicle access; and expand access to clean and reliable transportation in rural communities.

Accelerate the transition to a zero-emission transportation system that equitably benefits health. Decarbonizing transportation will bring immediate health benefits including cleaner air and more physical activity. To maximize health equity, federal and state governments can: increase funding for zero-emission public transit systems and active transportation infrastructure (e.g., walking, biking); strengthen fuel efficiency and pollution standards; expand state incentives to accelerate equitable electric vehicle access; and expand access to clean and reliable transportation in rural communities.

End the development of all new fossil fuel infrastructure and phase out fossil fuel subsidies as rapidly as possible, while ensuring a just transition. Ending new fossil fuel development will protect health and improve health equity. Policies must also minimize the health impacts of existing fossil fuel infrastructure. These efforts must be accompanied by investments to support workers and communities in the just and equitable transition to renewable energy.

End the development of all new fossil fuel infrastructure and phase out fossil fuel subsidies as rapidly as possible, while ensuring a just transition. Ending new fossil fuel development will protect health and improve health equity. Policies must also minimize the health impacts of existing fossil fuel infrastructure. These efforts must be accompanied by investments to support workers and communities in the just and equitable transition to renewable energy.

Target investments in adaptation to build healthy, resilient, and equitable communities. Investing in community resilience will prevent the worst impacts of climate change, strengthen public health and health care systems, and improve overall health outcomes. These efforts – targeted in the most burdened communities – must prioritize multi-sector strategies to strengthen health systems, build neighborhoods that buffer against extreme heat and other climate events, and redress historic harms of economic and social disinvestment.

Target investments in adaptation to build healthy, resilient, and equitable communities. Investing in community resilience will prevent the worst impacts of climate change, strengthen public health and health care systems, and improve overall health outcomes. These efforts – targeted in the most burdened communities – must prioritize multi-sector strategies to strengthen health systems, build neighborhoods that buffer against extreme heat and other climate events, and redress historic harms of economic and social disinvestment.

Scale up U.S. contributions to global climate change finance to support global health equity. Achieving the global goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C will protect health now and for future generations. Current financing from the U.S. and other high-income countries falls far short of what is needed to help all countries rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve this global climate target. The U.S. must fulfill and expand its commitment to increase U.S. contributions to global climate finance for clean energy, adaptation, and a just transition.

Scale up U.S. contributions to global climate change finance to support global health equity. Achieving the global goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C will protect health now and for future generations. Current financing from the U.S. and other high-income countries falls far short of what is needed to help all countries rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and achieve this global climate target. The U.S. must fulfill and expand its commitment to increase U.S. contributions to global climate finance for clean energy, adaptation, and a just transition.

State of Climate Change and Health in the U.S.

Climate change and its primary driver – burning fossil fuels – have created an accelerating health crisis.-01, -02 The health impacts in the U.S. are far-reaching and predicted to increase in the coming years. These impacts include heart and lung disease, infectious diseases, heat-related illness, poor pregnancy outcomes, sleep deficiencies, adverse mental health impacts, injuries, and death. Climate change also affects health through disruptions in health care delivery, education, employment and other social systems; population displacement; and societal-wide economic harm.-01, -02, -03, -04 Policy decisions rooted in structural racism and economic injustice place many communities at even greater risk (Box 1).

Climate change is an accelerating health crisis, but there are reasons for optimism. Promising climate solutions are available and momentum for climate action is growing. An equitable transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy sources will reduce air pollution and curb the threats of climate change – improving health, saving lives, and promoting health equity.

Producing and burning coal, methane gas, and oil creates harmful air pollution and releases greenhouse gases (GHGs) that cause climate change. The impacts of climate change are now upon us. In July 2022, nighttime temperatures were the warmest in U.S. history,-05 and nearly two-thirds of people across the continental U.S. and Puerto Rico were affected by drought.-06 Climate change has made recent extreme weather events in the U.S. worse, including megadrought in the West,-07 wildfires in California,-08 extreme weather and precipitation in the Gulf Coast,-09, -10, -11 warm ocean anomalies in the Pacific Northwest,-12 and extreme rainfall from hurricanes in Florida.-13

Communities and health systems across the U.S. face compounding health crises including the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, gun violence,-14, -15 racial injustice,-16, -17 and economic insecurity. Climate change and its health risks converge with these crises, furthering the urgent need for decisive action to protect health.

Box 1

The health impacts of climate change are not experienced equally (Appendix Table A). Climate change deepens health inequities rooted in systemic racism and economic inequity, and disproportionately harms communities of color, Indigenous communities, and people living in low-wealth communities. Structural racism amplifies inequities in climate change-related health impacts by increasing susceptibility and exposure to climate threats and reducing the adaptive capacity of communities targeted by discriminatory policies.-18, -19

For example, the racially discriminatory lending practice of redlining that began in the 1930s continues to impact the health risks from climate change today.-20 Historically redlined neighborhoods have more oil and gas wells,-21 higher levels of air pollution,-22 less tree cover and green space,-23 and hotter temperatures.-24 Their residents experience higher rates of adverse health outcomes such as heat-related illness, cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and poor maternal health outcomes.-20, -25, -26

The past forced migration of Indigenous people away from their traditional lands also places Indigenous communities at greater exposure to climate change threats today, as the lands to which they were forcibly moved are often hotter and drier.-26 Redlining and forced migration are only two examples of the many ways policy decisions reflect and perpetuate racial and economic injustice.

Many other communities and populations, such as children, pregnant people, older adults, LGBTQ persons, and people living with disabilities, are at increased risk from climate change due to a wide range of social, political, physiological, developmental, and behavioral factors (Appendix Table A).

Table 1

Air Pollution

- Indicator 3.3

In 2020, there were approximately 32,000 deaths in the U.S. due to exposure to ambient anthropogenic PM5. Of these, 37% were directly related to fossil fuel burning. - Indicator 4.1.4

In 2020, the monetized value of these deaths due to air pollution was estimated to be $142 billion (0.7% of the U.S. GDP), equivalent to the annual income of over 2.2 million people under average income in the U.S. combined.

Heat

Heat and Exposure to Warming

- Indicator 1.1.1

Average U.S. summer temperatures from 2017-2021 were 1.4°F (0.8°C) higher than the 1986-2005 average, and this is 0.5°F (0.3°C) above the global average increase during the same period.

Heat Exposure Among Sensitive Populations

- Indicator 1.1.2

Adults over age 65 experienced 137 million more person-days* of heatwaves, meaning that, on average, each older adult experienced an additional 3 heatwave days per year from 2012–2021 compared to 1986-2005. - Indicator 1.1.2

Infants under 1 year experienced 12 million more person-days* of heatwaves, meaning that each infant experienced, on average, an additional 0.24 heatwave days per year from 2012–2021 compared to 1986-2005.

Heat-Related Mortality

- Indicator 1.1.5

Heat-related mortality for people over 65 is estimated to have increased by approximately 74% from 2000-2004 to 2017-2021.

Economic Burden of Heat

- Indicator 4.1.2

In 2021, the monetized value of global heat-related mortality in the U.S. was estimated to be equivalent to over 850,000 people receiving the average U.S. income. - Indicator 1.1.4

In 2021, heat exposure led to the loss of 2.5 billion potential labor hours, a 36% increase from the 1990–1999 average . - Indicator 4.1.3

In 2021, $68 billion (0.3% of the U.S. GDP) was lost in potential income from reduced labor due to extreme heat .

Infectious Disease

- Indicator 1.3

From 1951-1960 to 2012-2021, the amount of time each year that Ae. aegypti mosquitoes are able to spread dengue increased by 48% . - Indicator 1.3

The contagiousness of dengue by Ae. aegypti (as defined by the basic reproductive number, R0) was 64% higher in 2012–2021 compared to 1951–1960 . - Indicator 1.3

The duration of malaria transmission season lengthened by 38% in U.S. lowland areas& in 2012–2021 compared to 1951–1960 . - Indicator 1.3

From 2003 to 2020, 5% more of U.S. coastal waters have become suitable for transmission of Vibrio cholerae .

Sea Levels Rise

- Indicator 2.3.3

Over 1.7 million people lived less than 3 feet above current sea level in 2020.

Indicators relevant to Brief Policy Recommendations

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- (Indicator 4.2.5)

In 2019, the U.S. was the second-greatest emitter of CO2 by both production- and consumption-based accounting, contributing 13.3% and 15.7% of the world’s production- and consumption-based CO2 emissions, respectively. In 2019, the U.S. was also one of the five leading emitters of PM5 by both production- and consumption-based accounting, contributing 2.9% of the world’s production-based PM2.5 emissions and 4.9% of the world’s consumption-based PM2.5 emissions.

Transportation

- (Indicator 3.4)

In 2019, electricity represented only 0.1% of total fuel use for road travel. Although this was a 24% increase in electricity use in transportation from the prior year, fossil fuel use in road transport declined by just 0.8% in 2019.

Adaptation

- (Indicator 2.2.3)

In a study of 50 urban centers in the U.S., only half were classified as moderately green or above in 2021.

* Person-days – the number of heatwave days multiplied by sensitive population count.

* Heatwave is defined as a period of two or more days where both the minimum and maximum temperatures are above the 95th percentile of the U.S. climatology (defined on the 1986–2005 baseline).

& Any part of the US that is <1500 meters above sea level is considered lowland.

All indicator data listed in this table come from the 2022 Global Lancet Countdown report. For detailed information regarding the indicators and indicator methodology, please see the global Lancet Countdown report Appendix.

Health Harms of Poor Air Quality

GHG emissions predominantly result from burning fossil fuels and agricultural production processes, activities that also contribute to dangerous levels of air pollution. From 2018 to 2020, more than 137 million people – over 40% of the U.S. population – lived in cities where air pollution levels exceeded U.S. regulatory standards.-27 This is especially concerning since health harms occur at pollution levels below the current standards and there is no known safe level of air pollution exposure.-28, -29, -30 An equitable and just transition to clean energy can result in significant, near-term health improvements by minimizing air quality-related death and disease,-31, -32, -33 with the potential to benefit disproportionately impacted communities.-34

Burning fossil fuels produces health-harming air pollution and leads to health inequities.

Air pollution from fossil fuel combustion harms every major organ system (Appendix Table B) and is a major cause of illness and death in the U.S. (Box 2).-35, -36 Children are uniquely susceptible.-37, -38 Data from the 2022 Global Lancet Countdown report suggests that in 2020, there were approximately 32,000 deaths in the U.S. due to exposure to ambient human caused particulate matter pollution (PM2.5), 37% of which were directly related to fossil fuels (Indicator 3.3, Table 1).-01 However, recent research suggests air pollution-related mortality in the U.S. may be much higher.-32, -39 Substantial economic costs are associated with the mortality that results from air pollution (Indicator 4.1.4, Table 1).-01

Air pollution from fossil fuel combustion includes particulate matter less than 2.5 (PM2.5) or 10 (PM10) microns, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitric oxide (NO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), traffic-related air pollution, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), and ground-level ozone (formed through chemical reactions from precursors from fossil fuel burning and other sources that include nitrogen oxides [NOx] and volatile organic compounds [VOCs] in the presence of sunlight).

Box 2

Immense scientific evidence is required to establish a causal link between an exposure and a disease. The American Heart Association determined that heart disease, which is the leading cause of death in the U.S., can be caused by exposure to PM2.5.-40, -41 The American Thoracic Society similarly determined that long-term exposure to PM2.5, especially from road traffic, causes childhood asthma.-42 In a landmark 2021 case in the United Kingdom, air pollution was listed for the first time as a cause of death for a 9-year old girl with asthma,-43 and there is a proposed bill in Utah to allow air pollution to be listed as a cause of death.-44 Thus, air pollution is a risk factor – similar to high blood pressure and diet – that can be modified to improve heart and lung health.-45

Air quality in most of the U.S. has consistently improved for the past several decades,-46 yet racial and income inequities in exposure to air pollution remain,-30 and in some cases are increasing.-47 Higher levels of PM2.5 are disproportionately concentrated in Black and African American, Asian, Latinx, and low-wealth communities than white and higher-income communities.-48, -49, -50 These disparities may be worse than previously estimated,-49 and persist despite the fact that white and higher-income communities produce the majority of pollution through higher consumption of goods and services.-51 Low-wealth households may also experience higher levels of harmful indoor air pollution from gas-powered stoves and appliances (Case Study on Health and Climate Impacts of Methane Gas in Buildings).

Climate change worsens air quality, increasing health risks.

Climate change worsens air quality by increasing the risk of wildfires, drought, elevated pollen levels, and extreme heat. Wildfire smoke accounts for a quarter of PM2.5 in the U.S. and as much as half in some Western states.-52 Droughts increase dust, which is a major air pollutant associated with health harms such as cardiovascular illness and possibly Valley Fever.-53, -54 Extended pollen seasons and higher levels of airborne pollen-55 are associated with respiratory health harms like asthma.-56 Higher temperatures increase the formation of ground level ozone, a pollutant that irritates lungs and results in more hospitalization and death.-57, -58, -59, -60 Climate change can also worsen air quality by slowing air pollutant removal in regions experiencing drought, increasing air stagnation, and lengthening the time between rainfall events that remove pollutants from the air.-57 Air pollution and heat interact to worsen health outcomes.-61

Heat-Related Illness

Climate change is causing the U.S. to experience hotter (Indicator 1.1.1, Table 1)-01 and longer warm seasons, and more frequent, longer, and more intense heat waves.-62 2021 was the sixth-warmest year on record,-63 and 2022 saw record-breaking heat waves across the U.S.-64 Average global temperatures are now 2oF (1.1oC) above pre-industrial levels,-65 and there is a 50% likelihood that the world will at least temporarily pass 2.7oF (1.5°C) within the next five years.-66 This 1.5°C threshold is the aspirational goal of the Paris Climate Agreement, but every fraction of a degree is predicted to be associated with more devastating impacts on physical and mental health.-2

Extreme heat harms health in many ways.

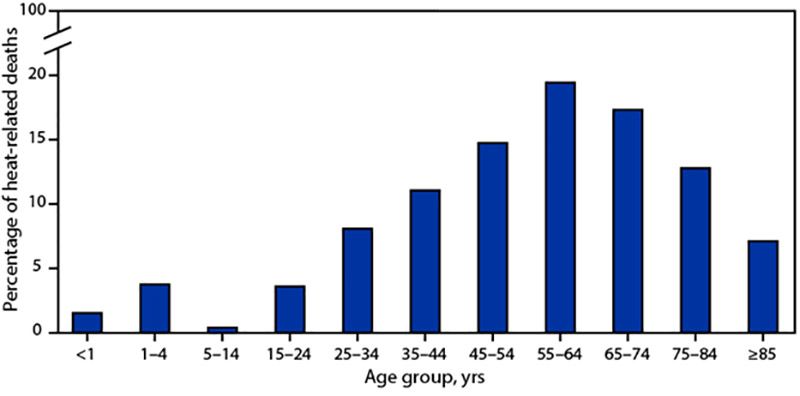

Everyone is at risk of dying from heat (Figure 1).-67 Heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the U.S.,-68 yet official statistics often underestimate the true burden. Recent research aimed at providing a more complete picture estimated that there are 12,000 heat-related deaths each year in the U.S.-69 The economic cost of these premature heat-related deaths is significant (Indicator 4.1.2, Table 1).

Figure 1. Heat-Related Deaths by Age in the U.S. 2018 – 2020

A total of 3,066 heat-related deaths occurred in the U.S. from 2018 to 2020. These deaths include only those defined by one of three medical diagnosis codes that attribute death to an exposure to natural heat (ICD10 codes X30, P81.0 or T67), thus missing many other pathways. This figure presents the percentage of total deaths that occurred within each age range; it does not provide heat-related mortality rates by age group. As the age groups presented above are not uniform, the figure may visually under-represent mortality in the youngest age groups.-67

Heat exposure causes widespread health harms-70, -71 including: acute and chronic heart, lung, and kidney disease;-71, -72, -73 adverse mental health outcomes such as mood and anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and increased suicide risk;-74, -75, -76 increased risk of preterm birth and stillbirth;-76 disrupted physical activity patterns;-77 worsened sleep;-3 heightened risk of seasonal allergies with complications for those with underlying lung conditions;-78, -79 and increased emergency department visits.-80 Extreme heat also results in lost labor hours and consequently lost income (Indicators 1.1.4, 4.1.3, Table 1).-01

Systemic social and economic inequities shape a person’s susceptibility, exposure, and adaptive capacity to extreme heat (Appendix Table A), and drive disparities in heat-related illness and mortality.

Susceptibility to heat-related illness is heightened among sensitive populations.

Children, pregnant people, older adults, and people living with illness are uniquely at risk from extreme heat (Appendix Table A). Young children and older adults are disproportionately harmed by warming temperatures (Indicators 1.1.2, 1.1.5, Table 1)-01 and older adults are disproportionately affected by heat-related morbidity and mortality (Figure 1). Extreme heat contributes to adverse physical and mental health impacts for children,-38, -81 impairs children’s ability to learn in school,-82 and makes it harder for them to safely play outdoors, undermining their physical and mental health and development. Extreme heat exposure in pregnancy is associated with preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth.-83, -84

Structural inequities lead to higher extreme heat exposure in some communities.

While everyone is at risk for heat-related illness, greater exposure to extreme heat leads to higher risk for some people (Appendix Table A). Economically and racially discriminatory policies shape extreme heat exposure (Box 1). Systemic marginalization and inequitable community investment practices result in urban design patterns, such as less green space, that amplify heat in some communities. People living in communities of color are more exposed to extreme heat and therefore more heavily impacted by heat-related sickness and death.-85 Areas with the largest projected increases in heat-related mortality are 40% more likely to be home to Black and African American people.-86 Heat-related mortality is also higher for non-U.S. citizens.-87 Exposure to extreme heat is higher for outdoor workers,-72, -88 people experiencing homelessness,-89, -90 and people who are incarcerated.-91

Adaptation strategies can prevent heat-related harm but are not equitably available to all.

Strategies exist at the individual, household, neighborhood, and city levels that can protect against extreme heat.-92 Yet there is inequitable access to effective, reliable, and affordable cooling strategies, including both community-level strategies that cool neighborhoods (e.g., greenspace) and adaptive responses to extreme heat events (e.g., cooling centers) (Appendix Table A).-93, -94 For example, in Philadelphia, there is less tree cover in communities of color.-95 Resource constraints may increase exposure to extreme heat and the risk of heat-related illness (Box 3). For example, low-wealth households are less able to access and afford health protective cooling (e.g., heat pumps, air conditioning).-70, -96, -97 More affordable cooling options, such as ventilation from fans or the outdoor wind, can be ineffective at very high temperatures.-92, -98

Extreme heat risk factors can intersect, compounding harm.

Many people and communities face multiple intersecting risks in which racial, economic, gender, environmental, and other social injustices overlap to deepen inequity. Climate threats further compound and amplify these risks. For example, due to the experience of chronic structural racism, maternal mortality rates are highest for Black and African American people in the U.S.-99, -100 Economic and racial injustice lead to Black and African American communities facing greater susceptibility and exposure to extreme heat. These overlapping forms of injustice compound, such that the association between extreme heat exposure during pregnancy and preterm birth may be stronger for Black and African American people and those in low-wealth communities.-101, -102

Box 3

The energy equity gap is a measure of differences in the threshold temperature at which households begin to use air conditioning (A/C). A/C is an energy-intensive cooling method that worsens climate change and contributes to warmer temperatures in urban communities.-18 However, A/C may also be necessary in extremely high temperatures and in the most impacted communities. As a result of financial constraints, many households may limit their use of electricity by not using or by deferring the use of A/C even under hot temperatures. This can increase the risk of heat-related illness. A recent study found a large energy equity gap such that low-wealth, and Black and African American households have higher temperature thresholds to begin using A/C compared to higher-income and white households.-96 Energy insecurity, or the inability to meet energy needs such as for cooling, is higher in Black and Hispanic households than white households.-103, -104 Low-wealth households that depend on electricity-powered cooling may face a higher economic burden as the need for cooling increases with rising temperature. The energy equity gap and the disproportionate economic costs of cooling-105 may be further exacerbated by the rising costs of energy and the economic challenges of 2022.

Recent legislative efforts, such as the Inflation Reduction Act, seek to reduce energy costs and reduce reliance on high-emission cooling strategies through funding for home electrification and energy efficiency retrofits in low-income and affordable housing.-106 There are also sustainable and low-energy strategies to reduce dependence on A/C and reduce energy poverty such as through urban greening and other community design strategies that cool neighborhoods (Figure 3).

Infectious Disease

Early evidence suggests that climate change may be linked to increases in the incidence of nearly 60% of infectious and pathogenic diseases worldwide, and there could be more than 1,000 different pathways by which climate change can increase the incidence of human infectious diseases.-107

Water-borne disease threats are increasing.

Warmer waters, in addition to other factors, create conditions favorable for the transmission of some infectious diseases. Vibrio spp. are a genus of bacteria that can cause different illnesses, including some with gastrointestinal symptoms and necrotizing fasciitis, increasing Vibrio spp. habitat suitability is linked to warming water temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns.-108, -109 The environmental suitability of Vibrio spp. has been increasing in U.S. coastal waters (Indicator 1.3, Table 1).-01

The rising threat of heavy flooding events increases the risk of stormwater overflow into sewer water systems, particularly combined sanitary and storm sewer systems,-110 contaminating drinking and recreational waters with dangerous levels of harmful bacteria.-111, -112, -113 This can lead to increased exposure to pathogens like Norovirus, E. coli, Salmonella, and Shigella-108, -114 and can result in higher rates of gastrointestinal illness. This has been observed in emergency department visits after flooding events in the U.S. (Critical Insight Box on Sea Level Rise and Health).-115, -116

Expansion of vector-borne diseases.

Climate change is contributing to disease-transmitting ticks and mosquitoes being able to live and thrive in new parts of the U.S. for a greater portion of the year.-2, -4 This has already contributed to increased vector-borne disease in the U.S., including Lyme disease-117 and West Nile.-118 In addition, the length of the season in which conditions are suitable for transmission of dengue, a vector-borne disease not currently common in most areas of the U.S., is increasing along with its contagiousness (as measured through the basic reproductive number, R0) (Indicator 1.3, Table 1).-01 Overall, children and pregnant people can be more susceptible to vector-borne diseases and resulting health complications.-38, -119

Mental Health Impacts

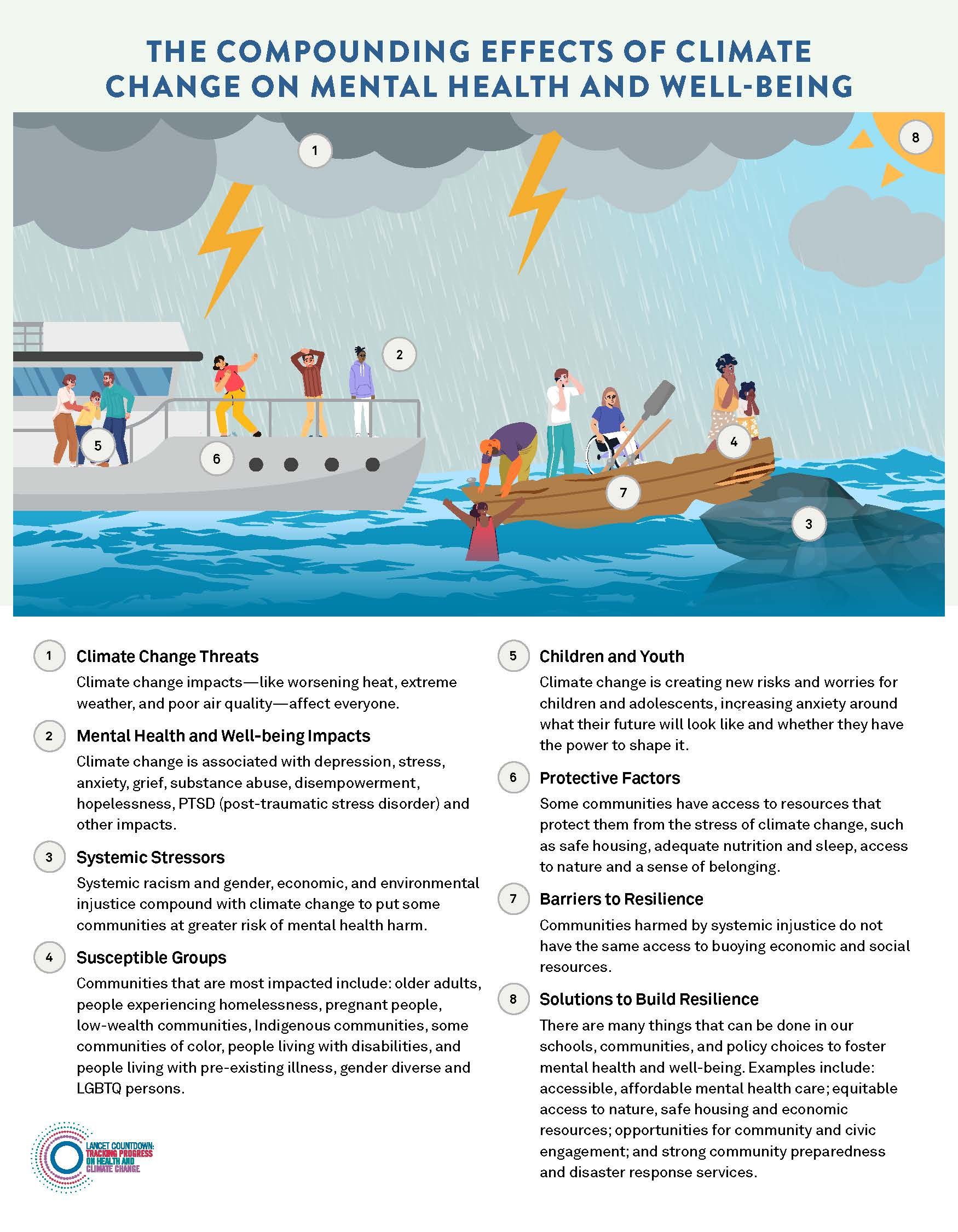

Climate change is harming mental health and well-being.-2, -120 Climate change impacts, including disasters, heat, and economic losses, are associated with increased risk of depression, stress, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, grief, substance abuse, disempowerment, and hopelessness.-121 Susceptibility to the mental health impacts of climate change is higher for communities with close ties to the land, including people living in rural and agricultural areas and Indigenous communities, and for children and young people.-4, -122 For additional susceptibility factors, see Appendix Table A. Systemic stressors, such as economic insecurity and discrimination, can exacerbate climate change threats to mental health and hinder equitable access to protective services and resources. There are individual, community, health care, public health, and policy solutions that can respond to and reduce the mental health impacts of climate change (Figure 2).-123, -124, -125

Figure 2. Compounding Effects of Climate Change on Mental Health and Well-Being. -74, -81, -85, -90, -126, -127, -128, -129, -130, -131, -132, -133, -134, -135, -136, -137, -138, -139, -140, -141, -142, -143, -144, -145, -146, -147, -148

Policy Recommendations to Advance Health and Equity in the U.S. Climate Change Response

The U.S. is at a turning point on climate change, and there are reasons for optimism. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) opened the door to nearly $370 billion in federal funding for cleaner, healthier energy and transportation systems; sustainable agriculture and forests; community-led resilience initiatives; and programs that address air and water pollution.-106 If fully implemented, the IRA is projected to reduce U.S. GHG emissions by around 40% below 2005 levels by 2030-149, -150 and benefit health by reducing air pollution.-149 The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act has the potential to contribute to GHG emissions reductions, and the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act will invest in clean energy technology research and development. Cities and states around the country are also passing new laws and scaling up investments in climate change action (Focus on Regions).

It remains to be seen how much these investments will impact health and environmental targets. Many U.S. policies remain inconsistent with health and equity goals, such as the IRA’s expansion of oil and gas leasing on public lands and the substantial state and federal subsidies for fossil fuels. The fossil fuel industry continues to influence climate policy and hinder climate action.-151, -152 In its 2022 ruling on West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Supreme Court limited the EPA’s ability to take a system-wide approach to regulating carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.-153

To keep temperature rise within livable bounds and protect against catastrophic health impacts, it is vital to reduce emissions now. This Brief outlines five policy recommendations to protect health and improve health equity in our national response to climate change. These strategies will reduce air pollution, minimize climate change-related health threats, and improve community safety and resilience.

Achieve a zero-emission energy sector and prioritize air quality improvements in the most impacted communities.

Achieve a zero-emission energy sector and prioritize air quality improvements in the most impacted communities.

The U.S. must rapidly implement policies to meet the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, which requires an estimated 57% to 63% reduction in its GHG emissions by 2030.-154 Cutting emissions in the energy sector, which accounts for a quarter of U.S. GHG emissions,-155 is critical. One study finds that the elimination of PM2.5 emissions from U.S. energy-related sources would prevent over 50,000 premature deaths each year and provide savings of more than $600 billion annually from avoided illness and death.-32

The IRA includes billions of dollars to expand wind and solar energy and help U.S. households and communities transition to clean energy.-106 Greater investments by all levels of government will also be needed in clean energy development, storage, and transmission. This is essential to meet the U.S. commitment to cut GHG emissions in half by 2030, reach 100% clean electricity by 2035, and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.-156 The cost of renewable energy has fallen, making clean energy competitive with conventional fossil fuel options.-157

Policy implementation can prioritize health and equity by focusing the clean energy transition in the most impacted communities. State, tribal, local, and territorial governments can expand equitable access to clean and healthy energy by setting 100% clean energy standards and legislating interim clean electricity targets; targeting clean energy infrastructure and investments in disproportionately affected communities; making subsidies for clean energy available to low-wealth, rural, and communities of color; adopting strong building electrification codes to accelerate implementation of home electrification and energy efficiency retrofits; and investing in renewable energy microgrids and other forms of community energy. The health care sector also has a substantial role to play in decarbonization (Critical Insight Box on Health Care Sector Role in Emissions Reductions).

Accelerate the transition to a zero-emission transportation system that equitably benefits health.

Accelerate the transition to a zero-emission transportation system that equitably benefits health.

The transportation sector is the largest contributor to GHG emissions in the U.S, accounting for around 27% of U.S. emissions in 2020.-155 In 2019, electricity represented only 0.1% of total fuel use for road travel. Although this was a 24% increase in electricity use in transportation from the prior year, fossil fuel use in road transport fell by just 0.8% in 2019 (Indicator 3.4, Table 1).-01

Transportation-related air pollution disproportionately burdens communities of color and low-wealth communities.-30 These communities also bear a disproportionate burden of pedestrian and bicycle fatalities;-158 depend more heavily on public transit systems;-159, -160 and benefit less from electric vehicle tax credits-161, -162 and investments in charging infrastructure.-163, -164

The U.S. is making historic investments to incentivize the manufacture, purchase, and use of electric vehicles; improve community walkability and road safety; and address the harmful impacts of traffic and transportation infrastructure on community life and livelihood (community severance).-106 However, the IRA does not include sought-after provisions such as tax incentives for electric bicycles, subsidies for public transit riders, or funding for public transportation system operating budgets and fleet electrification.-165

States can prioritize health equity in transportation by increasing investment in zero-emission public transit systems and active transportation infrastructure, like sidewalks and bike lanes, and by improving traffic safety. This will make it more affordable, convenient, and safe to use public and active transportation – improving air quality, increasing physical activity, and expanding access to essential services.-159, -166, -167

Additional strategies to maximize health in the transition to zero-emission transportation include: increasing state incentives for electric vehicles to accelerate access in communities most affected by air pollution; implementing more stringent fuel efficiency and pollution standards to reduce health-harming transportation emissions, such as through adoption of California’s clean vehicle standards;-168 requiring stronger state and local transportation emissions reduction targets and enhanced emissions tracking; and ensuring rural communities have access to clean and reliable transportation.

Box 4

Without an intentional focus on equity, climate change policies can create new risks, harm health, and deepen health inequities.-151, -169 Policies must be developed and executed in meaningful collaboration with communities to avoid harmful outcomes (e.g., inequitable distribution of air pollution; displacement and gentrification) and ensure equitable access to and benefits from mitigation and adaptation.-94, -170 Communities of color, Indigenous communities, and communities directly impacted by policy decisions must be engaged, in addition to the health community, in all stages of policy development and implementation. Policymakers should additionally integrate traditional knowledge and lived experience in the development of climate solutions.

End the development of all new fossil fuel infrastructure and phase out fossil fuel subsidies as rapidly as possible, while ensuring a just transition.

End the development of all new fossil fuel infrastructure and phase out fossil fuel subsidies as rapidly as possible, while ensuring a just transition.

The U.S. is the world’s leading producer of oil-171 and methane gas.-172 Current levels of fossil fuel production are inconsistent with global climate goals and must rapidly decline.-173, -174, -175, -176

Policymakers at all levels should end subsidies to fossil fuel companies – conservatively estimated at around $20 billion annually in the U.S.-177 These subsidies profit the fossil fuel industry,-178 enable more fossil fuel exploration and development,-179 lock in reliance on polluting energy, and hinder investments in clean energy.-180 The IRA, by opening public lands and waters for oil and gas leases and increasing subsidies for carbon capture technologies, also risks extending fossil fuel dependence.

Fossil fuel infrastructure is disproportionately placed in Black and African American, Indigenous, other communities of color, and low-wealth communities,-21 driving disproportionate adverse health impacts (Case Study on Health Impacts of Pollution from Oil and Gas Production).-181, -182, -183, -184 Ending new fossil fuel leases, infrastructure projects, and exports will achieve a safer climate future and will directly and immediately improve air quality and protect health. Stronger emission standards, improved emissions monitoring, and reduced emissions of methane and other harmful pollutants from oil and gas production can better protect the health of communities living near fossil fuel infrastructure.

This must be accompanied by investments to support workers and communities in the just and equitable transition to renewable energy.-185, -186 This can occur through support for the people and communities who will be economically impacted by the energy transition and those who live near fossil fuel infrastructure, for example through targeted workforce development, and requirements for local hiring, prevailing wages, and union jobs in clean energy development projects.

Decarbonization efforts must prioritize actual emission reductions today over achieving theoretical future negative emissions through carbon capture and storage/sequestration or carbon dioxide removal technologies. These technologies are costly, remain under-developed and unproven at scale, and can extend the use of fossil fuels.-151 If implemented without attention to health, these approaches may result in additional health harms and miss opportunities to maximize near-term, local improvements in air quality (Critical Insight Box on Health and Equity Considerations for Carbon Capture and Storage).

Expand investments in adaptation to build healthy, equitable, and resilient communities.

Expand investments in adaptation to build healthy, equitable, and resilient communities.

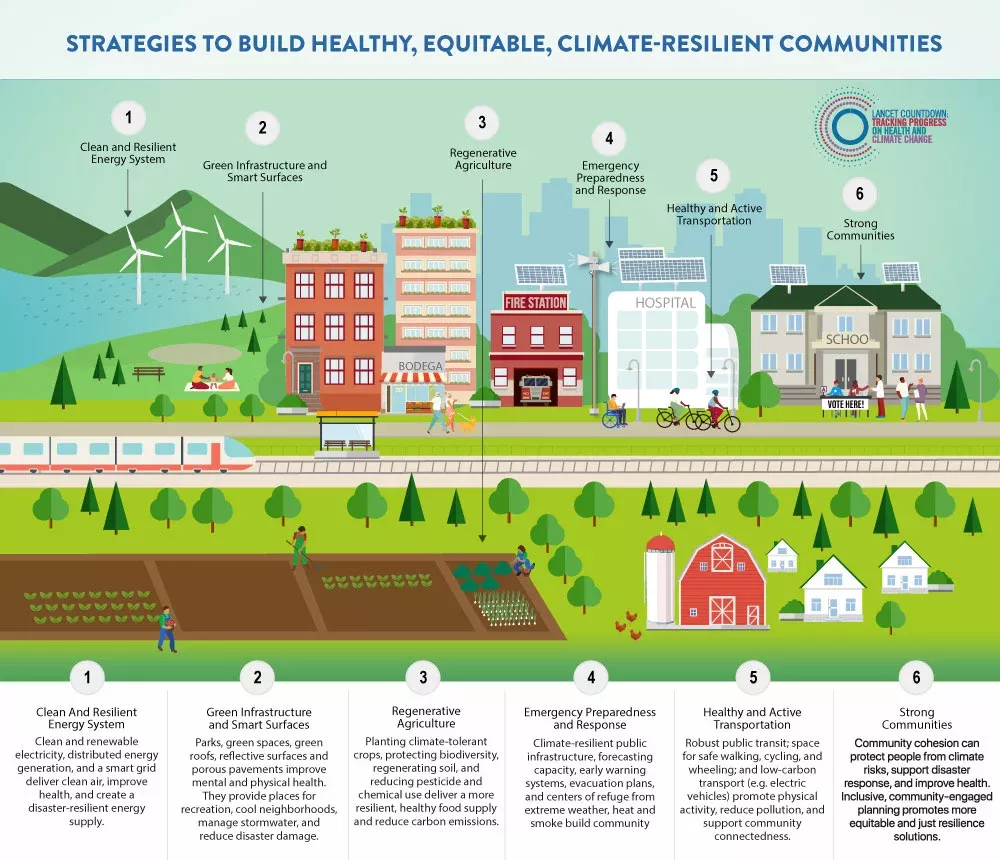

As temperatures rise, adaptation efforts that build community and health systems resilient to climate change are increasingly important (Box 4). Policies can mitigate the health risks of climate hazards-187, -188 by expanding green infrastructure, tree cover, and cool roofs and pavement;-92, -189, -190 designing neighborhoods to reduce traffic congestion and increase active transport;-158, -191, -192 expanding regenerative agricultural practices (Critical Insight Box on Climate Change and the U.S. Food System);-193 strengthening the resilience of public infrastructure including schools,-194 community energy systems,-195, -196 and health systems;-70 and building social cohesion (Figure 3).-197

These strategies have multiple health benefits. For instance, more green space cools urban areas, reduces air and water pollution, assists with flood control, provides space for recreation, improves mental health, increases physical activity, and reduces all-cause mortality.-132, -198, -199, 200, -201 In a study of 50 urban centers in the U.S., just half were classified as moderately green or above in 2021 (Indicator 2.2.3, Table 1).-01 State and federal investments in adaptation should prioritize the health and well-being of communities most susceptible to climate risks by investing directly in the most impacted communities.

Housing, transportation, energy, agriculture, and other agencies throughout the U.S. government are engaged in a whole of government approach to climate change. Public health agencies must work in coordination with these agencies – and with impacted communities – to maximize the health equity benefits of these efforts. Public health entities lack the levels of funding needed to address climate change.-202 Expanding funding for climate change and health will enable health partners to implement community climate resilience programs and participate actively in climate policy implementation.

Figure 3. Strategies to Build Healthy, Equitable, Climate-Resilient Communities.-152, -192, -193, -197, -200, -203, -204, -205, -206, -207, -208, -209, -210, -211, -212, -213, -214, -215, -216, -217, -218, -219, -220, -221, -222, -223, -224, -225

Scale up U.S. contributions to global climate finance to support global health equity.

Scale up U.S. contributions to global climate finance to support global health equity.

Achieving the Paris Agreement targets will benefit health in the U.S. and globally,-226 yet is only feasible with rapid emissions reductions in all high-emitting countries. Scaled-up investment in global climate action is essential to protect health and achieve global climate goals.-151 The U.S. is historically the world’s biggest contributor to cumulative GHG emissions,-227 and in 2019 was the second-greatest emitter of CO2 (Indicator 4.2.5, Table 1).-01

The U.S. must meet its commitment to support decarbonization, adaptation, and a just transition at home and in the countries most impacted by climate change. In 2020, high-income countries provided around US$ 83 billion of climate finance to low- and middle-income countries.-228 This is less than the US$ 100 billion commitment made in the Paris Agreement, a commitment that already falls significantly short of the need. The U.S. contributes proportionally less global climate finance than other high-income countries.-229

President Biden has committed to significantly increase U.S. contributions to global mitigation and adaptation, such as through the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience.-230 Congress must act to fulfill and expand these pledges.

International climate investments made by the U.S. can promote health and equity by supporting programs that reduce health-harming air pollution in the most impacted communities, mitigate and respond to climate change-related health threats, build climate-resilient health systems, and support the health response to climate-related disasters.

Conclusion

Climate change is already harming the health of people across the U.S., and rapidly transitioning to a zero-emission economy is essential to protect health and reduce existing inequities. The coming years present an opportunity to shape historic climate investments. If implemented with care, climate change policy can benefit health today and ensure a healthier and more equitable future for all people in the U.S., especially those who are most harmed by climate-related hazards. It is incumbent that the health community be part of climate change policy development and implementation to ensure that these efforts promote health, equity, and a just transition.

Acknowledgements

U.S. Policy Brief Authors: Naomi S. Beyeler, MPH, MCP*; Natasha K. DeJarnett, PhD, MPH, BCES*; Paige K. Lester, MA; Jeremy J. Hess, MD, MPH; Renee N. Salas, MD, MPH, MS.

*Signifies co-lead authors in alphabetical order

Additional Team Acknowledgements: Support, Logistics, & Review: Luke Testa; Kelly Phouyaphone, MPH; Infographic Design: Figure 2 – Huck Strategies; Figure 3 – Paige K. Lester and Danielle Crockett, BFA; Appendix, Additional Materials, and Website Design: Huck Strategies; Appendix Spanish Translation and Copy Editing: Juan Aguilera MD, PhD, MPH;Gabriela Haymes ; Copy Editing: Carissa Novak, MScGH; Laura E. Peterson, BSN, SM. Thank you to the Climate and Health Foundation for their generous support.

Review on Behalf of the Lancet Countdown (alphabetical): Anthony Costello, FmedSCi; Frances MacGuire, PhD, MPH; Marina Romanello, PhD; Maria Walawender, MSPH.

Review on Behalf of the American Public Health Association (alphabetical): Gillian Capper, MPH; Katherine Catalano, MS; Evelyn Maldonado; Mary Stortstrom.

Science and Technical Advisors (alphabetical): These science and technical advisors provided technical and review assistance but are not responsible for the content of the report, and this report does not represent the views of their respective federal institutions. Caitlin A. Gould, DrPH(c), MPPA; Rhonda J. Moore, PhD; Ambarish Vaidyanathan, PhD.

U.S. Brief Working Group Reviewers of Brief and Appendix (alphabetical):

Ploy Achakulwisut, PhD; Susan Anenberg, PhD; Mona Arora, PhD, MSPH; Madeleine Bartzak, MPH, RN; Jesse E. Bell, PhD; Aaron Bernstein, MD, MPH; Laura Bozzi, PhD; Robert Byron, MD, MPH; Linda D. Cameron, PhD; Gillian Capper, MPH; Amy Collins, MD; Cara Cook, MS, RN, AHN-BC; Tim Cronin; Shelbi Davis, MPH; Michael A. Diefenbach, PhD; Kathleen Dolan, MPH; Caleb Dresser, MD, MPH; Kristie L. Ebi, PhD, MPH; Matthew J. Eckelman, PhD; Donald Edmondson, PhD, MPH; Luis E. Escobar, DVM, MS, PhD; Howard Frumkin, MD, DrPH, MPH; Meghana Gadgil, MD, MPH, FACP; Julia M. Gohlke, PhD; Ilyssa O. Gordon, MD, PhD; Chelsea Gridley-Smith, PhD; Yun Hang, PhD, MS; Adrienne L. Hollis, PhD, JD; Emily Blair Katzin; Philip Landrigan, MD, MSc; Rachel Lookadoo, JD; Melissa Lott, PhD, MS; Edward Maibach, MPH, PhD; Ezra Markowitz, PhD; Leyla Erk McCurdy, MPhil; Anna Miller, MPH; Amruta Nori-Sarma, PhD, MPH; Nick Obradovich, PhD; Lisa Patel, MD, MS; Jonathan Patz, MD, MPH; Ellen Peters, PhD; Rebecca Philipsborn, MD, MPA; Stephen Posner, PhD; Liz Purchia; Heidi Honegger Rogers, DNP, FNP-C, APHN-BC; Caitlin Rublee, MD, MPH; Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH; Mona Sarfaty, MD, MPH; Liz Scott; Emily Senay, MD, MPH; Jodi D. Sherman, MD; Cecilia Sorensen, MD; Sarah Spengeman, PhD; Keri K. Stephens, PhD; Vishnu Laalitha Surapaneni, MD, MPH; J. Jason West, PhD; Skye Wheeler; Kristi E. White, PhD, ABPP; D’Ann L. Williams, DrPH, MS; Carol Ziegler, DNP, NP-C, APHN-BC; Lewis H. Ziska, PhD.

U.S. Policy Brief Appendix, Additional Materials, and Infographics Authors

Infographic Authors (traditional academic authorship or alphabetical):

Figure 2: The Compounding Effects of Climate Change on Mental Health and Wellness – Katherine Catalano, MS; Naomi S. Beyeler, MPH, MCP; Shelbi Davis, MPH; Natasha K. DeJarnett, PhD, MPH, BCES; Paige K. Lester, MA; Rhonda J. Moore, PhD; Nick Obradovich, PhD; Heidi Honegger Rogers, DNP, FNP-C, APHN-BC; Luke Testa.

Figure 3: Strategies to Build Healthy, Equitable, Climate-Resilient Communities – Paige K. Lester, MA; Naomi S. Beyeler, MPH, MCP; Katherine Catalano, MS; Michael A. Diefenbach, PhD; Kathleen Dolan, MPH; Howard Frumkin, MD, DrPH, MPH; Rachel Lookadoo, JD; Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH; D’Ann L. Williams, DrPH, MS.

Appendix Authors (traditional academic authorship or alphabetical):

Appendix Table A: Factors that Shape Climate Change Susceptibility, Exposure, and Adaptation – Natasha DeJarnett, PhD, MPH, BCES.

Appendix Table B: Key Fossil Fuel-Related Air Pollution and Health Linkages – Natasha DeJarnett, PhD, MPH, BCES.

Health and Climate Impacts of Methane Gas in Buildings – Laura Bozzi, PhD; Sarah Spengeman, PhD.

Health Impacts of Pollution from Oil and Gas Production – Ploy Achakulwisut, PhD; Gillian Capper, MPH; Liz Scott.

Health Care Sector Role in Emissions Reductions – Madeleine Bartzak, MPH, RN; Amy Collins, MD; Ilyssa Gordon, MD, PhD; Emily Senay, MD, MPH.

Health and Equity Considerations for Carbon Capture and Storage – Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH; Naomi S. Beyeler, MPH, MCP; Emily Senay, MD, MPH; Vishnu Laalitha Surapaneni, MD, MPH.

Climate Change and the U.S. Food System – Lewis H. Ziska, PhD.

Appendix Table A: Factors that Shape Climate Change Susceptibility, Exposure, and Adaptation – Natasha DeJarnett, PhD, MPH, BCES.

Appendix Table B: Key Fossil Fuel-Related Air Pollution and Health Linkages – Natasha DeJarnett, PhD, MPH, BCES.

Additional Material Authors (traditional academic authorship or alphabetical):

Focus on the Northeast – Madeleine Bartzak, MPH, RN; Tim Cronin, MPA; Michael A. Diefenbach, PhD; Caleb Dresser, MD, MPH; Chelsea Gridley-Smith, PhD; Melissa Lott, PhD, MS; Mona Sarfaty, MD, MPH; Emily Senay, MD, MPH; D’Ann L. Williams, DrPH, MS.

Focus on the Midwest –Rachel Lookadoo, JD; Jesse E. Bell, PhD; Robert Byron, MD, MPH; Jonathan Patz, MD, MPH.

Focus on the South – Carol Ziegler, DNP, NP-C, APHN-BC; Naomi S. Beyeler, MPH, MCP.

Focus on the West – Naomi Beyeler, MPH, MCP; Robert Byron, MD, MPH; Lisa Patel, MD, MS; Heidi Honegger Rogers, DNP, FNP-C, APHN-BC; Linda Rudolph, MD, MPH.

THE LANCET COUNTDOWN

The Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change is an international, multi-disciplinary collaboration that exists to monitor the links between public health and climate change. It brings together 38 academic institutions and United Nations agencies from every continent, drawing on the expertise of climate scientists, engineers, economists, political scientists, public health professionals, and doctors. Each year, the Lancet Countdown publishes an annual assessment of the state of climate change and human health, seeking to provide decision-makers with access to high-quality evidence-based policy guidance. For the full 2022 assessment, visit https://www.thelancet.com/countdown-health-climate.

THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION

The American Public Health Association (APHA) champions the health of all people and all communities. It strengthens the public health profession, promotes best practices, and shares the latest public health research and information. The APHA is the only organization that influences federal policy, has a nearly 150-year perspective, and brings together members from all fields of public health. In 2018, APHA also launched the Center for Climate, Health and Equity. With a long-standing commitment to climate as a health issue, APHA’s Center applies principles of health equity to help shape climate policy, engagement, and action to justly address the needs of all communities regardless of age, geography, race, income, gender and more. APHA is the leading voice on the connection between climate and public health. Learn more at www.apha.org/climate.

Recommended Citation: Lancet Countdown, 2022: 2022 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Policy Brief for the United States of America. Beyeler NS*, DeJarnett NK*, Lester PK, Hess JJ, Salas RN. Lancet Countdown U.S. Policy Brief, London, United Kingdom, 20 pp.

Executive Summary State of Climate Change & Health Climate Change and Structural Inequities New Science Health Harms of Poor Air Quality Exposure to PM2.5 Heat-Related Illness The Energy Equity Gap Infectious Disease Mental Health Impacts Policy Recommendations – Achieve Zero-Emissions – Accelerate The Transition – Phase Out Fossil Fuel – Expand Investments – Scale Up U.S. Contributions Conclusion Acknowledgements

CASE STUDY 1: Methane GasCASE STUDY 2: Pollution From Oil & GasCRITICAL INSIGHT 1: Sea LevelCRITICAL INSIGHT 2: Health Care SectorCRITICAL INSIGHT 3: Carbon CaptureCRITICAL INSIGHT 4: Food System